Greetings from scenic State College, PA! The trees are barren, the temperatures are single digits, and I am in heaven. It’s been nearly 16 years since I last saw snow, so this trip has been a wonderland of salt-encrusted sidewalks and ploughed piles of greyish white looming in the corners of parking lots. Will I eat shit on my first patch of ice? Who knows! Truly a mysterious and magical time of year.

With the weather providing some extra time to stay warm and cozy, I thought it would be good to give a general rundown of the site. What are its purposes, goals, thoughts, feelings, dreams, etc. etc.? There’s a lot to discuss here, but basically I'm envisioning the site as a semi-personal space to share my projects and work without the anxiety and dread that comes from doing that on the academic career track. That’s not to say I won’t be doing research here, but I thought it’d be nice to get back to making things for fun, so I’m using this website as a way of encouraging that. And now that blogging is dead, it also seemed like the perfect time to make a blog that like five people will read. But hey, I’m glad you’re here, reader number four.

Of course, special interest dumping and sharing cat pics are not my only reasons for making this site. Back around 2020, I visited a retro game store near Orlando, Florida, and was browsing through their selection of big box PC titles from the 1980s and 1990s. While they didn't have anything especially unusual, particularly bulky copies of Nihon Falcom's Sorcerian and Sierra On-Line's King's Quest VI caught my attention. Upon pulling them from the shelf, I noticed both games had a distinct heft. While big box games from this era often contained multiple floppy disks and oversized manuals that significantly add to their weight compared to console games and PC releases in the late 1990s and early 2000s, this went beyond what I was accustomed to handling. I asked the owner if I could take a look, and I found both contained notes that their previous owners had created while playing both games. I've seen a lot of writing on video game cartridges from rental stores or codes written in manuals, but these documents were extensive and detailed interpretations of the games that contained numerous personal touches. In that moment, I found myself peering into an old diary, but the intimate details were specifically about one player's experience with learning to analyze, adapt, and prevail in these games. These notes, however, offered more than simple rundowns of how to most effectively bonk enemies, and also shed light on the player's personality and interests through smaller details such as handwriting, organization, tone, style, etc. I quickly purchased both, and thus began my personal quest to start recording various notes and inserts left by players in video games.

As I built out my personal log of these items, I began to realize that the people I spoke to in and around the retro game scene were also interested in and excited by these materials. Where eBay and auction sites primed me to expect that these artifacts would be seen as junk lowering the overall value of old video games, I instead found people genuinely attached to these practices who wanted to see what I had found and share their own notes and writing. These encounters were inspiring, and moved my thinking towards building a public archive of notes, maps, and other miscellanea left behind in secondhand video games. More than this, these conversations also prompted me to start considering why (beyond nostalgia) these materials might be of interest to players. One friend at the time joked that I should also include the bugs, mold, and other...erm "natural" personal relics that they found in old games at their store. As compelling as that pitch was from an eco-media angle, I decided to keep my focus on the things that people wrote on and around video games (for now). Thus, the "Memo...rial Museum" was born.

So, for anyone without direct history with these practices, I suspect the first question might be: "why do these documents matter to players?" Truthfully, this was and remains a question of mine as well. My personal answer to this question starts with my background as a game studies person with feet in games and media studies as well as in writing and rhetorical theory. In my dissertation (eugh), I focused on the ways that we might think of playing video games as a form of writing or composing. If games are just static code until they're booted up and played (Alexander Galloway - Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture), in what ways can we analyze and interpret the act of playing? For me, writing was one of those ways, and much of my published work looks at various forms of this. I was drawn to the these notes and documents, then, because they provide a very clear example of play and writing intersecting. My interest was amplified because these materials are also nearly absent from the major lines of writing on video game writing. Belabored caveat: Putting forth any kind of taxonomy is always questionable work frought with cases that clearly escape and blur the neatly drawn boundaries between classes, so simply for the purposes of illustrating some of these major lines I would outline the following key areas in writing on video game writing:

Platform and Corporate Communication

Writing on Game Studies Research and Scholarship

Writing on Video Game Learning and Literacy

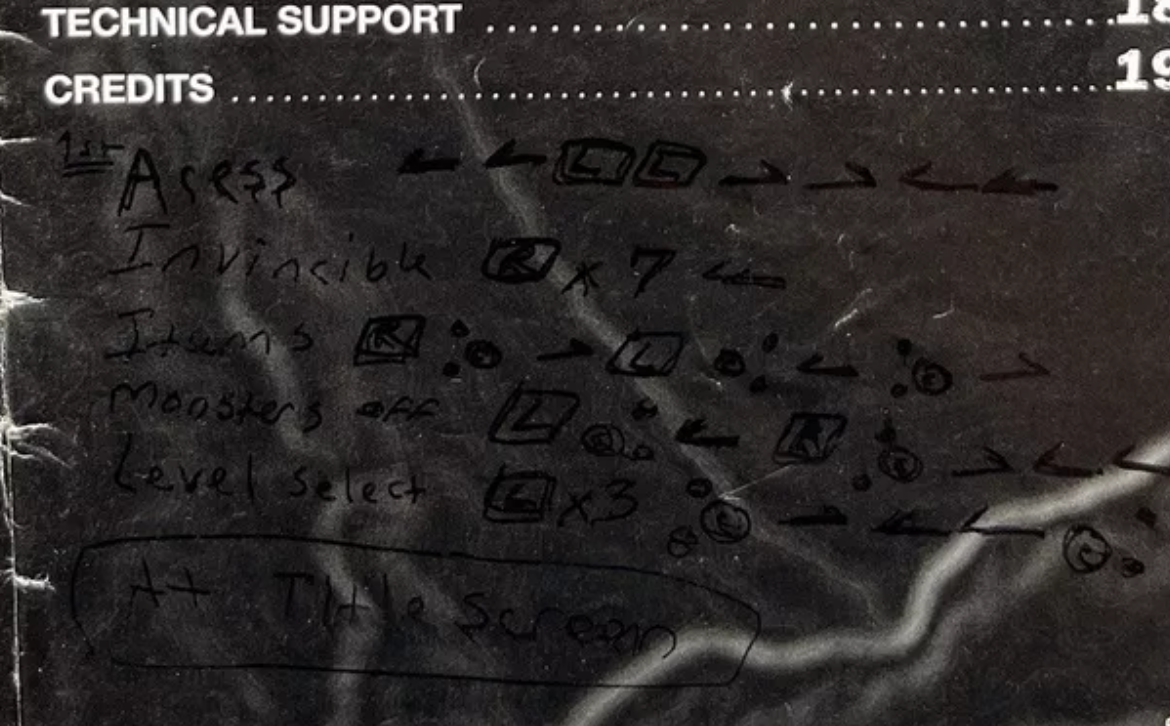

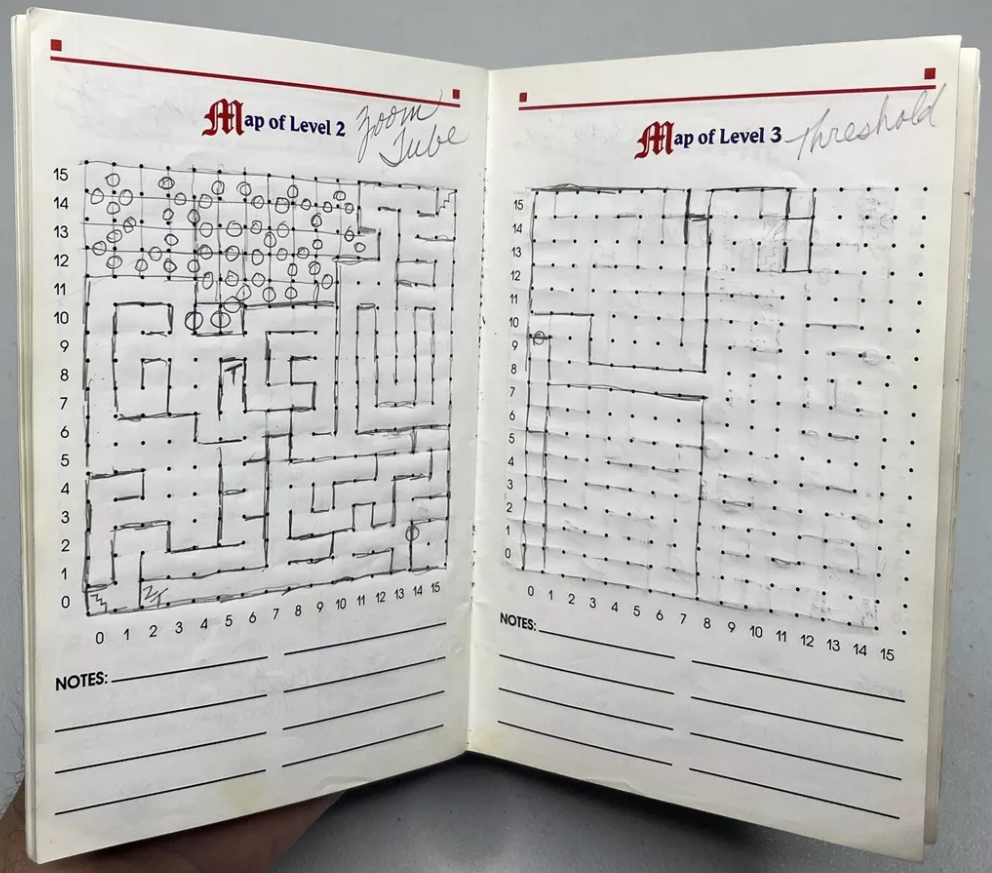

Anxious as offering these examples makes me, I think it's an...okayish place to start while also underscoring the fact that so many more examples, categories, and subcategories of writing on video game writing are out there. Anyway, my point here is that with some minor exceptions, these kinds of documentation practices don't have much of a place in the existing literature. Part of why, I suspect, these forms of writing have only received small attention is because they share more in common with their analog gaming ancestry and exist in an interstitial space between digital and tabletop/wargaming. Jon Peterson's analysis of physical materials and gaming in Playing at the World has been immensely useful for chipping away at the allure of these materials and pointing towards various avenues for analysis. Many of the handmade maps included in Peterson's work share significant overlap with the maps that players create for digital game spaces, both deploying graph paper and similar techniques for representing topography and key points of interest. Unsurprisingly, we can also use similar methods to read them. Dungeon maps in particular have deep resonance with video game maps as games themselves are often "twisty little passages" (Nick Montfort - Twisty Little Passages: An Approach to Interactive Fiction) of hallways and corridors through which players stumble. Peterson suggests we can read these maps through their literary associations as the dungeon enters tabletop's and wargaming's spatial lexicon through literary works like Conan, Treasure Island, and The Hobbit. These works present the dungeon and maze as spaces of mystery containing unusual and surprising destinations and rewards, their ascents and descents simulating a rhythm that lure us deeper with promises of perils and spoils (134). Much in the way that Charles Brockden Brown's underground in Edgar Huntly symbolizes more than a simple chain of caverns and instead uses this space to represent the unconscious, so to do these maps draw us in with a certain kind of spatial rhetoric of desire, discovery, and the unknown (Figure 2). This reading can extend beyond maps to also speak to handwritten codes. In the "topography" of video game manuals and inserts, codes are often found in the backmatter of manuals or on their margins, similarly liminal spaces that elicit the feelings of moving beyond or outside of orderly visual and spatial logic into the unknown. Codes are particularly interesting given what they do: unusual button entry sequences often granting significantly altered states of being in game spaces. Thus, the presence of these arcane "words" lurking in the margins of manuals, much like MISSINGNO. on the edge of Cinnabar Island, gestures towards alternative realities coursing beneath and around those that are officially recognized (Figure 1). These elements are, of course, also often positively associated with game experiences and may present one path for answering "why" these materials still are viewed with interest today.

Figure 1: Cheat Codes Written at the Bottom of a Duke Nukem 64 Instruction Manual

Figure 2: Maps Drawn in a Swords and Serpents Instruction Manual

So there is both cultural history and signifiers at play in the question of "why" these materials have resonance for players. Yet where does this all begin? In my read, this practice goes well beyond even tabletop and wargaming. While I cannot give an exact date for when documentation practices with video games began, I am also hesitant to do so as it almost certainly connects to broader cultural ideas about seeing, organizing, and representing space explored by Don Ihde in Postphenomenology. Ihde, analyzing Leonardo da Vinci's schematics and diagrams, argues that these precursors invent a disembodied "third eye" perspective that becomes associated with an "objective" way of seeing. According to Idhe, da Vinci strived for maximum visibility and the erasure of positionality, which I think we can see especially in the maps produced by players. Yet these documents are far from fully objective diagrams without positionality, re-introducing the subject through the unique styles of re-translating game spaces. Moreover, if we read them not simply as writing that ends on the page but rather as a link between player and character demonstrated by what players choose to include and exclude in their notes, these notes present ways of being rather than simply seeing. Given these distinct qualities that aren't exactly derived from da Vinci's legacy, I need to do more work researching various points of influence to really pin down an exact origin. I'd also be just as happy to simply acknowledge that the beginnings (like so many beginnings) are in fact multiple and extend from numerous writing traditions.

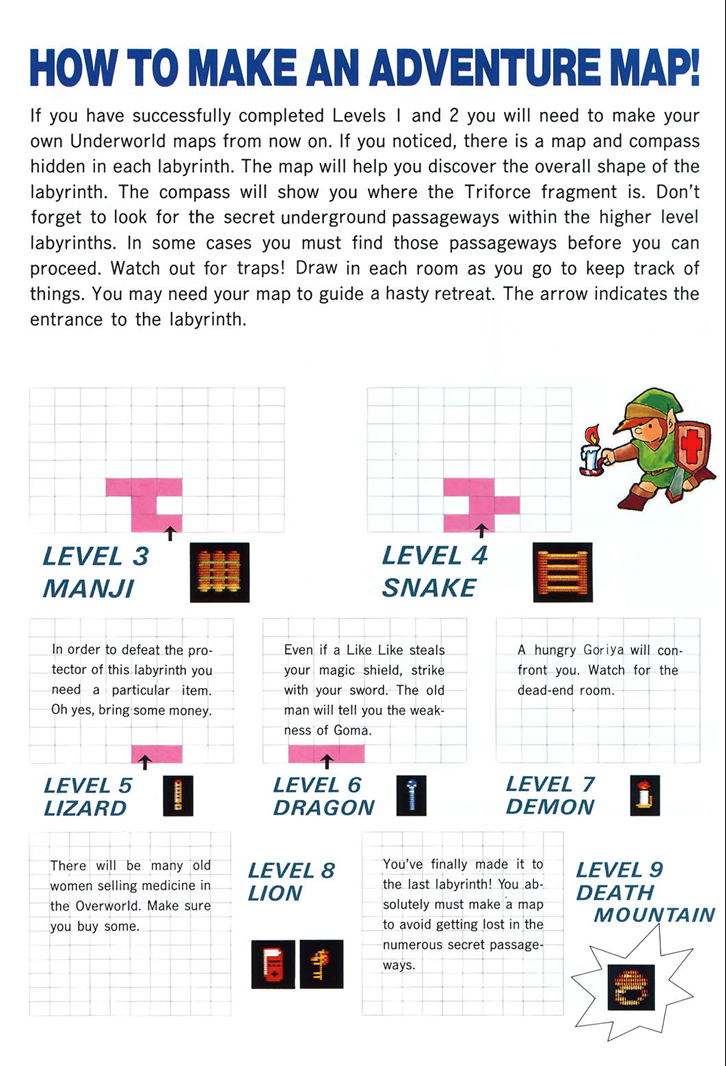

Returning to the semi-present, video game manuals during the 1980s and 1990s time often included a section in the last couple of pages for notes where players could record high scores, clues to solving puzzles, passwords, small maps, basically anything they might want to write. Some game manuals, such as the one included with Nintendo's The Legend of Zelda for the Nintendo Entertainment System, even included instructions for how to make useful notes that could assist players at a later date:

Figure 3: The Legend of Zelda Map Making Instructions

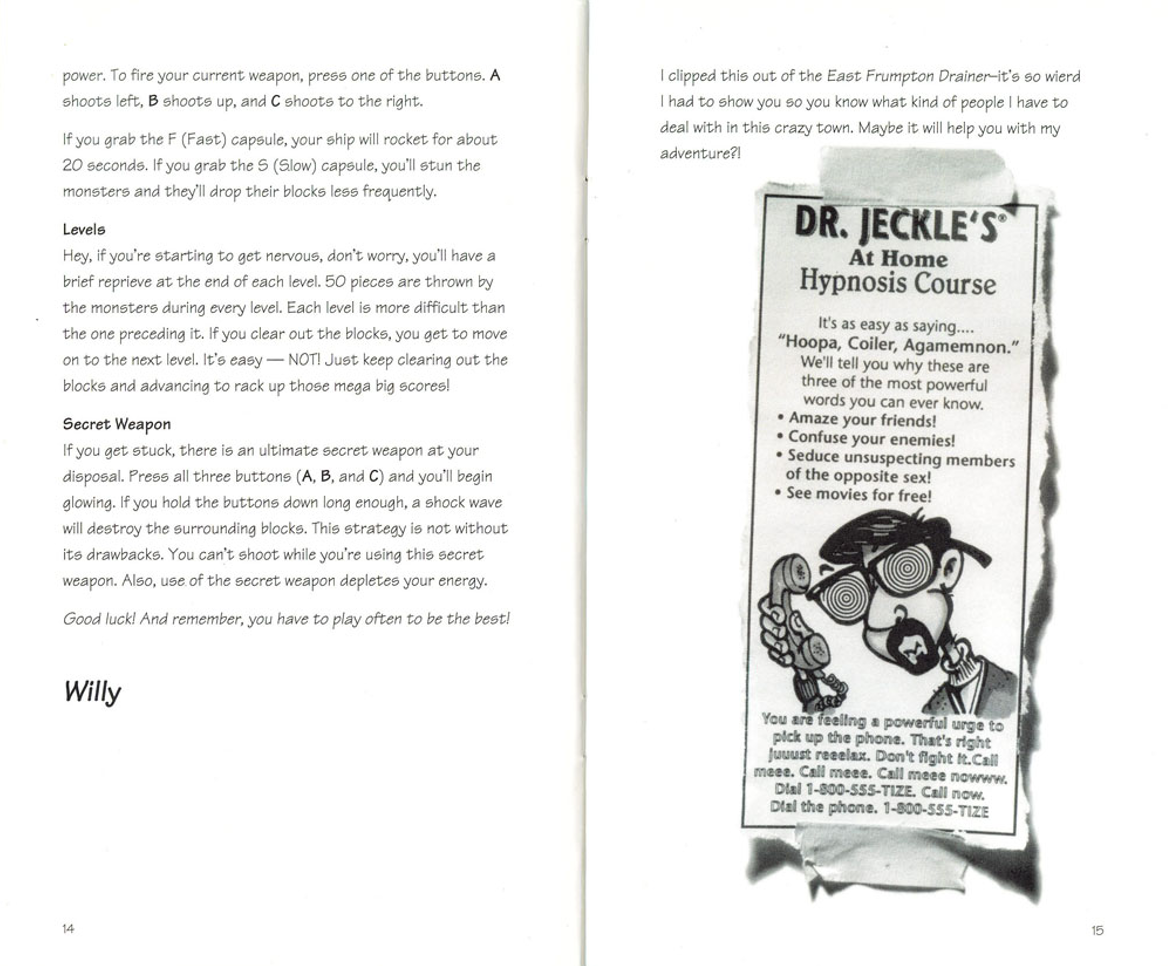

This practice became something of a writing genre unto itself, and later games such as Dynamix's The Adventures of Willy Beamish and Rare's Donkey Kong Country would provide their own forms of citation of and meta-commentary on this style of writing.

Figure 4: The Official The Adventures of Willy Beamish Instruction Manual Written and Designed in the Style of Handmade Player Notes

Figure 5: Cranky Kong Commenting on the Inclusion of a Notes Section (also referred to as the "Memo" section) in the Donkey Kong Country Manual

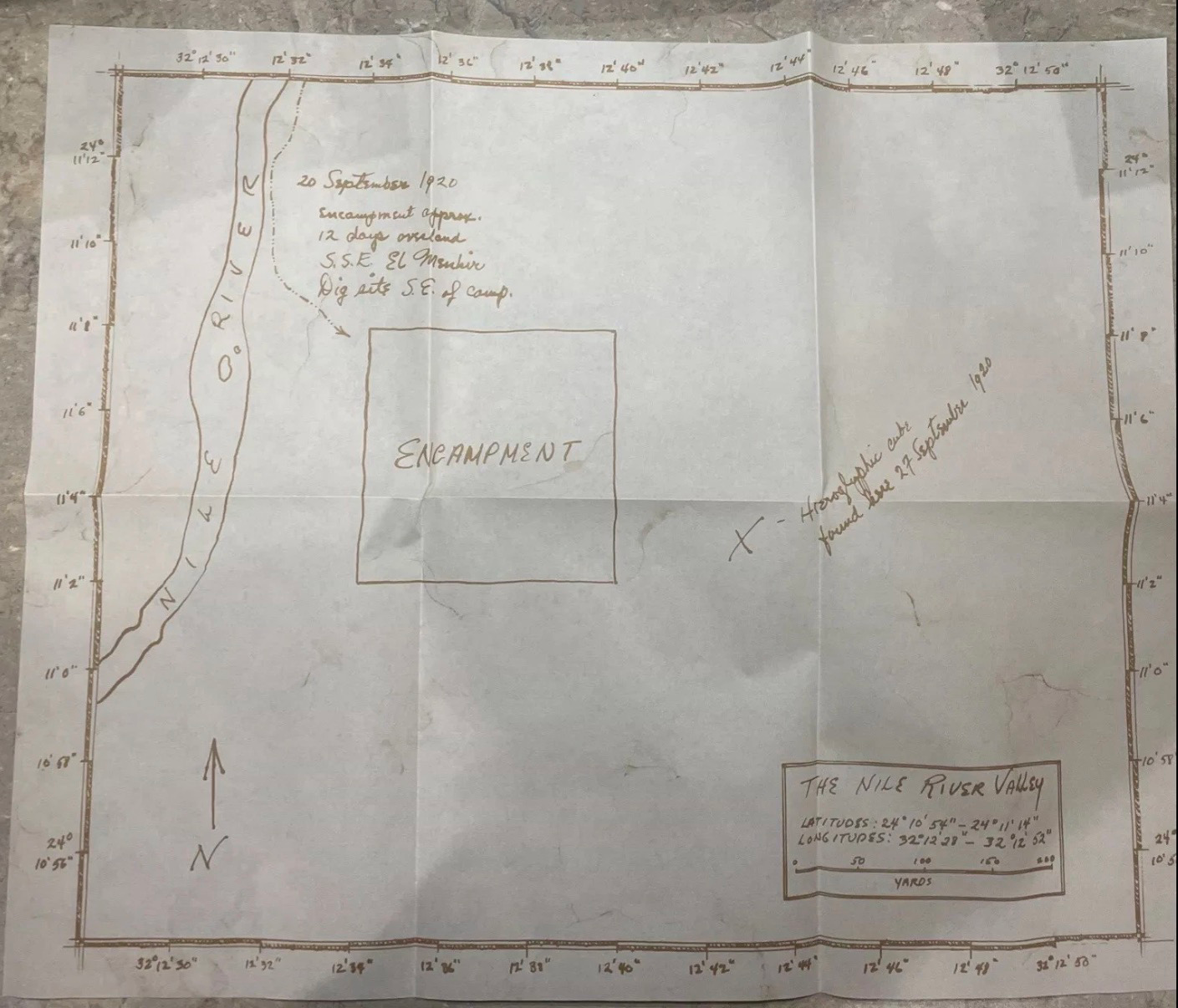

Meanwhile Infocom's Infidel and Sir-Tech's Advanced Dungeons and Dragons: Eye of the Beholder included pre-made maps and notes that directly mimic the mapping and notetaking practices that players had settled into around that time and makes it part of the in-game characters’ own archaeological writing practices:

Figure 6: Infidel Insert Resembling both Translation and Gameplay Notes

Figure 7: Infidel Map Insert

Figure 8: Advanced Dungeons and Dragons: Eye of the Beholder with Map Insert and Annotations

Whereas both Infidel and Advanced Dungeons and Dragons: Eye of the Beholder include pre-filled maps for players to reference without making their own, other PC games such as Darkspyre and Wizardry would pre-emptively include graph paper and note pads in anticipation of players writing and sketching their way through these spaces:

Figure 9: Darkspyre Included Graph Paper 'Scratch' Pad

Figure 10: Wizardry Inserts Featuring a 'Map Plotting Pad'

Even more recent releases such as Diablo 3 and Starcraft 2 include notepads as pack-in objects for players to write with, providing an interesting opportunity to compare how many players used the note materials included in these more recent titles with those included in older pc titles.

As manuals (and physical materials entirely) have slowly faded from the mass market, this practice has taken on new forms of documenting and curating gameplay in the form of Let’s Plays, YT commentary, online posts, etc. Yet this video- and posting-based content is largely made for a different media environment, one that is almost always created with an audience and algorithm in mind. So these documents have both a past and a future. Early forms of player writing, however, are much more personal and intimate, sometimes revealing things about a player’s experience that they would never express in a public forum.

Earlier, I suggested that we might think of them as a kind of “player diary.” But is this the best phrase to describe these materials? Recently, Hayes Madsen shared these images on Bluesky from Hironobu Sakaguchi’s Twitter account:

Sakaguchi tweets that these images are “From the FF3 planning document.” These images share an incredible amount in common with those created in, for instance, one player’s playthrough of Sorcerian. Although Sakaguchi’s documents are more tightly organized and labeled, the annotation format and ways of representing game spaces displays many similarities. Yet there are key differences here as well. Sakaguchi used these to construct and compose Final Fantasy 3’s game world, while players’ maps emerge from a practice of deconstructing these spaces and then reassembling through forms of literacy that make sense to them as they return to re-read these documents. While Sakaguchi's documents can tell us something about how he built Final Fantasy 3's world, player documents tell us how they individually read game spaces/mechanics/story. Their notes are not just direct translations of the game space, but also expressions of my own ways of reading/thinking that the game has been filtered through. These personal qualities are inscribed in the ways they record this information. Effectively, these layers of translation, then, leave us with an interesting case of the palimpsest from the original design document as it passes from designer, into game, to player, and back onto page…although, I’m not sure if I really consider it an erasure or an expansion. Perhaps we might call these “playing documents” to compliment the other side of Sakaguchi’s “planning document.”

Figure 11: Hironobu Sakaguchi Planning Document Tweet

Figure 12: Planning Documents

Figure 13: Planning Documents

Figure 14: Planning Documents

Alright, so, I think this roughly outlines why people might have interest in these materials, but it raises an additional question: why make an archive? Well, in addition to sharing these materials, part of my motivation here is because these materials are vanishing. Physical game media is disappearing, and with it many of the surfaces and objects that players either use to write on or store their handmade notes in. Additionally, the rise of collector markets has resulted in mixed treatment of these materials. Some collectors and resellers see these materials as important documents from the time and retain them to attract buyers who are interested in preserving a piece of that history. These materials remain as they allow resellers to market the "aura" of a specific era to increase the object’s perceived value. Another part of the collectors market, however, sees handwriting and old notes as decreasing the value of older games. The value for these folks is in a pure form of the object itself with any traces of the role it played in previous lives "cleaned" away or completely erased. And while this latter group may make the former appear somewhat noble, it’s important to remember that money is the core motivation of both groups, so much like ROM hoarders who refuse to allow preservation groups to dump beta and unreleased games, they could refuse to share these materials to maintain an allure of mystery around a physical game’s contents. I am, however, happy to note that I have not personally encountered such a situation yet.

Finally, why now? What can this project offer us in our current moment, and what might it speak to? I've thought a bit about this and believe that now, more than ever, it's important to create projects that highlight and celebrate human creativity and ingenuity. In these documents, we see how people developed heuristics and deployed methods for solving complex problems and puzzles without the need for things like Microsoft's Gaming Copilot telling players what to do. These documents affirm that inventing techniques for interpreting and reading game spaces is a vital and deeply rewarding activity wrapped up in what makes play and video games enjoyable. While AI evangelists want to convince us that we need a chatbot to tell us how to think and breathe, these materials say fuck that with immense joy. This project, I think, shows people delighting in anti-AI tasks such as thinking about, working through, experimenting with, and solving challenges. It is evidence that there is pleasure in developing the tools and methods necessary to address difficult situations, and that there is tremendous power in pencil and paper. More than this, it is a reminder of what we can accomplish against spaces and forces that are both computational and confrontational. In short, in these documents I find signs of resistance and hope.

Considering these factors, I thought I would start seeking out and scanning/photographing these kinds of writing. To go way back to the start of this post, the other motivation for this website is thus: provide an archive of player diaries/playing documents.

Since I began this work, the always wonderful Video Game History Foundation has created a fully searchable database of their magazine scans which includes some examples of these materials. It’s great seeing them formally acknowledged in the VGHF library, but there’s still so much more out there! So, I’d like to end this post repeating the call in post 0. If you have any materials like this and want to see them preserved in the archive, please email them! I will be sure to credit and include any information that you’d like to see posted. My dream is to have this site become a place where future researchers and people generally interested in gaming culture from these eras can see this form of interaction that players were engaging in with video games before it becomes lost to time. Maybe they’ll have some cool stuff to say about them. Maybe a kid who is now an adult will see some maps they drew and have a personally resonant moment. Who knows? Dear fifth reader from 2097, how is it? Are these materials still interesting? Are you still making little doodles and notes about video games? I hope so.

Special thanks to Dr. Hong-An Wu and Dr. Josef Nguyen for inviting me to give a talk on this project at The Studio for Mediating Play at The University of Texas at Dallas in 2024. This project would not be what it is today without the space to share, discuss, and develop these thoughts. I remain deeply grateful for their support and encouragement. Going forward, I’ll start talking a bit more directly about specific objects in the collection and different ways we might interpret, study, and engage them. Until next time.